Panama to Green Cove Springs by Sail – March 2011

I recently completed a life-goal of mine; to complete a long passage by sail. Please understand that I have done a fair amount of travel by sea – about a hundred thousand miles during my naval career – but those were all on large vessels. I have also done a fair amount of sailing in my time but that consisted mostly of racing and day sailing. No, I wanted to make a real passage in a real sailboat; traveling, not tourism. Fortunately Tor Pinney gave me that chance. I had declined an offer to go with him on a previous voyage much to my regret, so when offered a chance to accompany him on a journey to bring Silverheels up from Bocas Del Toro, Panama to Green Cove Springs, Florida, a small town on the St. John’s River I signed on as crew. The trip was to be about 1500 sea miles or so; since Silverheels typically covers about 125 miles a day or so Tor figured it would take about twelve days of sailing plus time spent in port between legs of the journey; two to three weeks total.

The flight down to Panama was uneventful but that did not prevent me from being nervous about it. I had to change airports in Panama City to catch a local flight back north a hundred miles to Bocas. Because I had to change airports, I thought it would be more difficult than it turned out to be. The taxi driver drove me right to the other airport which was a former U.S. Airforce base. I had a bit of a layover before boarding a smaller prop plane to my final destination. Panama City is not only a very big city, it is thoroughly modern. Bocas del Toro is neither. Tor collected me at the little airstrip there and we walked back to the harbor. On the way I was charmed to see goats in the back of a passing pickup truck/taxi. Welcome to rural Panama.

The flight down to Panama was uneventful but that did not prevent me from being nervous about it. I had to change airports in Panama City to catch a local flight back north a hundred miles to Bocas. Because I had to change airports, I thought it would be more difficult than it turned out to be. The taxi driver drove me right to the other airport which was a former U.S. Airforce base. I had a bit of a layover before boarding a smaller prop plane to my final destination. Panama City is not only a very big city, it is thoroughly modern. Bocas del Toro is neither. Tor collected me at the little airstrip there and we walked back to the harbor. On the way I was charmed to see goats in the back of a passing pickup truck/taxi. Welcome to rural Panama.

We spent a day doing some preventative maintenance – things like going aloft and checking the fittings on the masthead (Tor’s job) and scrubbing months of growth off the anchor chain (my job). This was necessary because otherwise then nasty marine growth that had grown on the chain in the months Tor had been anchored here would fill the boat with a nasty stench.

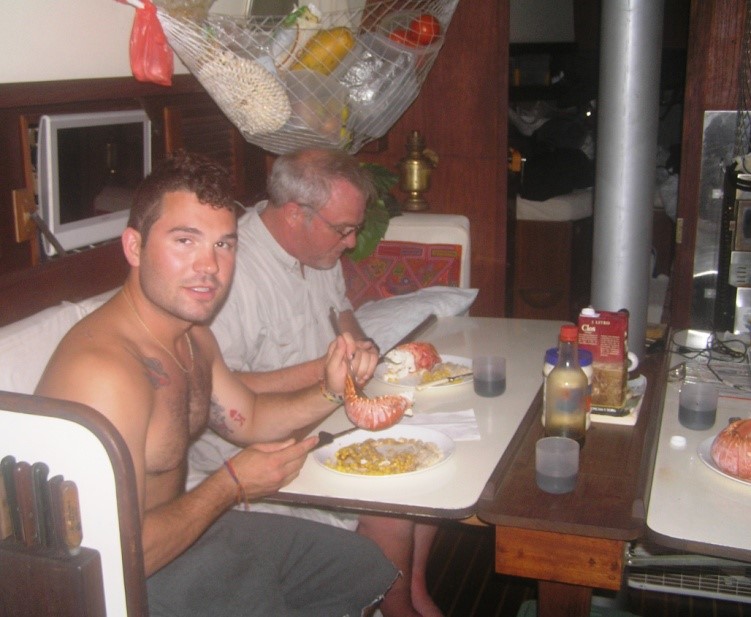

That job done, we set off into town to finish provisioning Silverheels with fresh food. Tor had already bought preserved food so we had relatively little to buy, mostly things like bread, fruit, and eggs. Our third crewmember also joined us. Zack is a vibrant and gregarious young man in his mid 20’s. He had spent some time as a fisherman off Alaska then did some international bumming around, eventually winding up in Bocas. He was glad for a chance to get a ride back to the US. His enthusiasm and spirit of adventure was a real addition to the crew. While Tor and I are somewhat more reserved, to Zack a stranger was just a friend he had not met yet.

We slipped out of Bocas del Toro around 0230 on St. Patrick’s Day. As we entered the channel we could see the lights of the bars and discos on the shore and hear the distant music. It would be a while before we would see civilization again. We left so early because Tor wanted to make our first stop at a small islet where we could hole up for a day or so. Tor wanted to have the sun up and behind us when we entered the lagoon so he could spot any coral heads that would rip out Silverheels’ bottom. That meant we needed to have a late morning/early afternoon arrival there and the time/distance required us to either leave late in the day and dawdle along or very early and make a normal passage.

We navigated the channel out and were in open water by daylight. I stayed up with the first watch while the others caught a much-needed nap. On a long passage you snatch sleep like a new mother, trying to avoid getting too tired for fear of being exhausted when a crisis erupts. I was enjoying the brisk wind which was unfortunately in the wrong quarter. That meant we would be almost beating into the wind for the next day and a half. And I was, as usual, somewhat sea sick which to me is more an annoyance than a debilitating illness. I enjoyed the brisk spray and observed the sea life. I was charmed to see the smallest dolphins I have ever seen, not more than a meter or so in length. They looked like Spinner Dolphins which are not all that large to begin with but these were very small- about three feet long. I wondered if they were perhaps juveniles, but I saw no others; just three or four of these lucky omens, playing off our bow wake.

Tor is an experienced sailor and navigator. We were able to beat north, periodically aided by the engine, and were find a secure anchorage between two tiny islets he had picked out as our first stopping point. We navigated between treacherous coral heads with Tor on the bow giving me directions as we motored slowly in to our anchorage. We stayed there three more days waiting for the wind to settle down and shift to a more normal westerly flow. From there we had another day’s run to another set of small islands called the Hobbies where we spent two nights, again waiting for a break in the weather. Finally we made the long run up, around Cuba and up the Florida coast to Jacksonville, in one continuous run.

- The Western Caribbean and its ‘Desert Islands’

The west side of the Caribbean Sea is bounded by Central America. Unlike the steep volcanic mountainous islands of the south eastern end of that sea, the islands at the west end tend to be low and fringed with shallow coral reefs which stretch offshore of the mountainous jungles of the mainland for over 2,000 miles of coastline that stretch along Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Belize and Mexico. In general, most of the area is not yet heavily visited by cruise ships and is not a major tourist destination. That means that the people tend to make their living on things other than tourist dollars; there are certainly visitors – young backpackers from all over the world come to stay at inexpensive hostels and hotels, enjoying the friendly locals and more rural lifestyle. (This is not to say that there is not a vibrant night life; parties and dancing at local hot spots go on until dawn almost every night.)

The islands we visited on our trip were tiny, remote, and beautiful. Tor wisely chose to stay a few extra days at our island anchorages due to adverse winds and squally weather. These little pieces of paradise provided a welcome break as well as giving us a chance to meet local fishermen who camp out on these little (3-4 acre) bits of land protected by tropical reefs.

The few people were transient – mostly fisherman camping out for a few days before making a run with their catch of fish, lobster, and conch back to San Andres Island, the largest inhabited island in the area. One of the islands did have a ‘garrison’ of a dozen Colombian soldiers who maintained a navigation light and communications building.

The second set of islands we visited was used to store many thousand lobster traps during the off season. There we met an exception to the transients – Antonio. He told us he had been living there in his simple one room house for six months. He loved it out there in the middle of nowhere.

- How do you live at sea? What do you do on a passage?

We spent 17 days aboard Silverheels, the last six of them continuously underway. Although at 42 feet she is not a small boat that is a small area for three men to inhabit for three weeks, especially when you consider that the first 15 feet or so of the bow is not really usable underway – the motion is too severe. Fortunately the crew was compatible – that makes a huge difference in the cruise. Captain Tor was very considerate, especially considering he had to welcome two large strangers into the small world he had inhabited by himself for the past eleven months. Further, Tor likes things done his way; this was not a problem for me because, frankly Tor’s way was the almost always the best way. His patience was deeply appreciated.

We spent a total of five days and nights at anchor with the remainder underway. We laid up to primarily to wait for more favorable winds but to give ourselves a rest, clean up the boat, and see the sights. After all this was more than a point to point transit. At anchor we relaxed, made better meals, and explored the islands where we were anchored. The fisherman on these little islands were generally just camping out while they spent a few days out trying to fill their boats although Anthony told us he had been living in his little house in the Hobbies for six months! We traded a little with some of the locals exchanging beer for fish and lobsters. Zack convinced them to take him out fishing with them one day. He came back tuckered out with a sunburned back from diving with them in search of something to catch. Zack is a pretty good snorkeler but these guys totally outclassed him – professionals vice a talented amateur. They were impressed that he would even try and took to young Zack; as I said he is friendly and personable. The crew of the boat Zack rode in invited us to have dinner with them the night before we left their island. We had coconut rice (freshly shaved coconut boiled in the water with the rice) and a turtle they had caught that day. It was an interesting meal.

Underway things were much simpler as things at sea tend to be. Except for the all important weather reports you are completely cut off from the rest of the mundane world. You stand watch, making sure the self steering is keeping the boat on course and that we do not collide with a merchant ship. When you are not on watch you eat, sleep, read and think.

There is plenty of time for that, especially at night when it is too dark to read and the others are generally asleep. Sleep is a big deal – watches are especially important at night when everything is more difficult and dangerous. It is fascinating to observe how fine sea swells on a sunny afternoon transform into dark menacing waves at night. Since each of us had at least four hours of night time watches we took every opportunity to catch naps during the day. Even a 15 minute power nap helps to keep you alert on those long quiet mid-watches from midnight until 0400. The morning watch (0400-0800) was my favorite watch during the hours of darkness. It was easier to get some good sleep since you could retire after your watch at 2000 the night before and get almost eight hours in. Best of all was the joy of watching the day begin at sea. At first all you notice is a faint hint of light in the east; then suddenly those dim, dangerous waves previously visible no more than a few feet from the transom are once again just a series of swells. The transition seems to occur in abrupt steps – all at once everything is revealed by the coming sun. Long before the sun actually appears everything is once again visible, clear, and simple. Sunrise brings with it a rise in my spirits. The second half of the watch, unlike the other nighttime watches, seems to fly by.

Allowing the wind and currents propel you over a substantial distance is a wonderful teaching experience. It brings you into closer contact with the planet, promotes patience, and gives you a real opportunity to think. I feel it is necessary to retreat from the day to day turmoil periodically to ponder deep thoughts. Being at sea also provides time to read (I read eight books on this passage) and talk about “things” both trivial and serious. Too often our modern life gives us no opportunity for contemplation.

- Rocking and rolling

One inescapable aspect of going to sea on a small boat is the way the boat is affected by wind and wave. There are normally three aspects of movement: pitch – the up and down motion fore and aft; yaw – the side to side movement; and roll – back and forth. There are two other axis of motion as well: heave – straight up and down as propelled from below; and acceleration/deceleration as the boat surfs down waves only to abruptly stop as it hits an oncoming wave at the bottom of at trough. On the first night out from Bocas Del Toro we have the full range of all five as we plowed close hauled to the wind into what is called a ‘confused and lumpy’ sea. That means there is no real rhythm to the motion, just desperate clutching to hang on as the boat moves this way and that unexpectedly and with some violence. It was all enough to make even a seasoned mariner sick – four times.

Even after seas calm down a small boat will move around a fair amount. This means that getting around on the boat, especially below decks, requires you to keep a hand on something or else risk being thrown against sharp and/or solid objects. Some of us were better at moving around below than others. Tor and Zack referred to my early efforts to move around below decks as “water buffaloes on ice.” In addition to stumbling about there is the problem of things not staying where you put them. With almost everything tipping (except the stove which was on gimbals) if you want something to ‘stay’ you will need to hold it in place. Here is how you get a plate out of the storage locker: whilst holding yourself in position with one hand, open the latch holding the locker door with the other hand, let go of the locker door and reach in to get the plate, let go of the hand holding you in place when the locker door whips viciously around and slaps you in face, stagger to the cabin sole as the ship lurches unexpectedly, and watch the door slam shut while wishing you had something prehensile to help out. You do eventually learn how to cope with the fact that you cannot depend on gravity alone to keep things where you put them.

There is one other element of a boat’s motion and that is a real danger: falling overboard. If you go overboard, unless someone actually sees you go into the water you are likely going to die. If you fall over at night you are almost certainly going to die. That means anytime you are outside the cockpit underway you need to treat the edges of the deck with the same respect you would give to the edge or a five story building – a five story building that moves around a lot.

- Food underway

Eating on a 42 foot mono-hull sailboat underway can be a challenging enterprise; especially if it is a bit rough. Cooking in these conditions is a challenge. Most of us have become used to prepackaged foods that are slipped into a microwave. Unfortunately microwave ovens consume too much battery power to be routinely used underway. That makes a gimbaled stove top with fiddle rails a necessity.

Simply keeping the pots and pans over the propane flame is the least of your problems. Galleys are, by the nature of boats, cramped. Counter space is very limited and treacherous as items tend to slide about if not carefully placed and watched vigilantly. By default the cook is constrained to at most two pots; a one pot meal is better yet. Since preparing cooked food is so difficult, most of the time only one hot meal is prepared a day. Breakfast is catch as catch can: a piece of fruit, some bread with peanut butter and honey, or whatever else is quick and easy. Lunch is usually either sandwiches or tuna fish (with mayo of course) and chips, sort of a dip your own sandwich. Even in rough weather, especially in rough weather, that hot meal is deeply appreciated.

Some people are better at cooking underway than others. Zack turned out to be an absolute wizard at fixing something up for the rest of us when things turned turbulent. He also knew how to prepare the fish we caught or traded for with the local fishermen. He took the Mahi Mahi we caught and turned it into a feast; he even took the ‘scraps’ that did not fit in the pressure cooker and fried them up as superb appetizer. Tor, as a wise and experienced old salt, waited until the conditions moderated to take his turn in the galley. He produced great spaghetti pasta dish and an absolutely delicious black bean soup that fed us for two days. Tor is a big fan of using the pressure cooker on a boat; it is faster, uses less propane, and keeps the food securely locked in the pot until it is ready. Oh, yes, and it makes creating a good hot meal a lot easier.

The biggest single advantage of cooking underway is the fact that the people you are feeding will almost certainly be hungry. Well, at least after the first day or so.

- The ‘Necessities’

Using the bathroom or ‘head’ (the proper nautical nomenclature) on a sailboat requires the balance of an acrobat, concentration of a Zen master and the judgment of Solomon. Men have the option of standing up and going over the side which is what we did most of the time, looping an arm around a sturdy bit of fixed rigging like a shroud. This is not without risk – see the comment in the paragraph above on the perils of being a man overboard. And perching on a little toilet seat in a tiny head while the boat is ‘lively’ is not something anyone looks forward to. This is not to mention the challenge of operating the flushing mechanism after you are done. All in all it makes constipation seem a blessing.

- Homeward bound

When you are at sea for a while even the sight of distant land is of interest. We enjoyed spending the day with the dark hills of Cuba off the starboard beam. There was real excitement when we first saw the distant towers of first Miami then Ft. Lauderdale while we rode the Gulf Stream north. This excitement was highlighted by a chance to first text then call friends and family as the cell phone signal reached out to us. The final afternoon at sea became tedious as the winds obstinately freshened and blew exactly from the direction we needed to be sailing. The Gulf Stream, heretofore our four knot ally, responded to the wind against its flow like a cat having its fur rubbed the wrong way; forming sharp, steep waves for Silverheels to crash into. Even though we were not making much progress through the water, the water was moving north at a brisk four knots on its way to warm the British Isles. By late afternoon, though, Tor had had enough and engaged the engine to head us toward the mouth of the St. John’s River which we entered at first light on a Sunday morning. I had entered the river many times before, but on a destroyer bound for Mayport. This time we sailed right on by the naval base near the river’s mouth and continued on all morning up the St. John’s River.

Entering the world after being isolated at sea is a slightly surreal experience. Here we were coming in from a long sea voyage mingling with weekend fishermen and Sunday pleasure boaters. Motoring up a busy river on a gorgeous Sunday, surrounded by people, is amazingly different than the lonely reaches of the open ocean. Our conversation turned to steak dinners – big ones. When we arrived at our desired destination, The Landings, a riverside collection of bars, shops, and restaurants, we managed to mooring right in front of a steak house. There was a talent contest going on and The Landings was packed with shoppers and people out having a good time. I found the abrupt transition from isolation to crowds of strangers to be a bit disorienting. But by the time we sat down that evening a table with Tor, Zack, my sister Dianne, and her husband Lamar we were back to being as close to normal as I guess we get. The next day Zack was off to his next adventure.

Two days later Tor and I sailed Silverheels to what will be her rest home for the summer: Green Cove Springs. We had an absolutely lovely sail with gentle cool breezes off our beam almost the entire way. As we sailed by the mouth of Ortega River where I grew up I could not help remembering how I used to swim, paddle, row, and sail a variety of small floating objects. Now here I was, out on the ‘big river’ in the kind of sailboat I used to dream about. And this portion of my voyage was the simple part – Tor hardly needed my help; he was just taking me along to snag the buoy at the end of the run. I appreciated the final ride though; an almost perfect day sail. We parted ways at the marina where we first met. Tor was surrounded by friends who were delighted to have him back. We shared a final Balboa beer together and then Lamar was there to take me back to Dianne’s.

All adventures eventually end.